Harry Devonport

(Click any thumbnail image to view full size)

Family

15 year old Harry appears on the 1901 census living at 107 Hucknall Lane, Sutton-In-Ashfield, Nottingham. This side of the road has been demolished at some point since that time. Only the even numbered houses remain. He and his 18 year old brother, Harold, are both working at one of the local coal mines. Harold was a "hewer" and Harry was a "pony driver". Pony driver was usually the first job given to boys joining the industry, who did this for 1-2 years before moving onto heavier work. The pit ponies and their drivers were responsible for moving the coal around in tubs on the narrow guage railway. The ponies were stabled underground, but usually well cared for, although based on an 8 hour day, their life span was generally only 3 1/2 years, compared to an expected 20 years of above-ground work. A hewer was a traditional "miner", drilling and digging and loosening rock and coal within the mine. It was hard and dirty work. Along with Harry and Harold were their sisters Jane (13) and Hilda (9). Their father, Elijah (50) was also a hewer in the coal mine, providing for his wife Elizabeth (49) and the rest of the household.

By the 1911 Census, Harry, now a hewer in the mine, is living at 37 Idlewells, Sutton-In-Ashfield, Nottingham. There is now a shopping centre on this site. He was living there with two female lodgers. His father had died 5 years before, in 1906. It's probable that his mother had also died, forcing him from the family home. His brother Harold had been married in 1904, and already had two children and his own home.

1901 Census - Devonport family

1911 Census - Harry Devonport

1911 Census - His brother, Harold, and his family

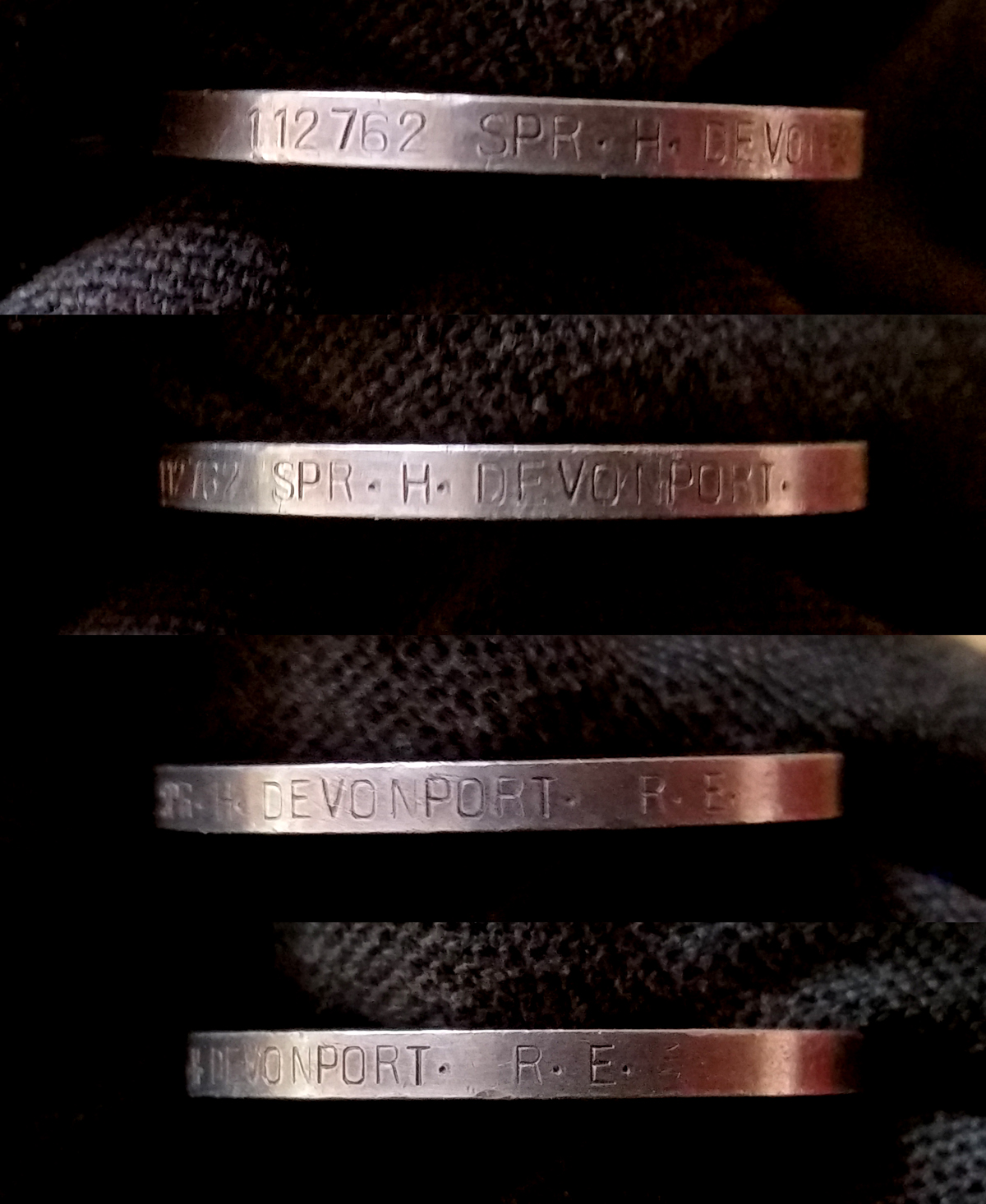

Harry DEVONPORT (Sapper)

112762, 171st Tunneling Company, Royal Engineers

British War Medal

Harry joined the army on the 1st September 1915, and due to his experience in mining, was immediately placed into the 171st Tunnelling Company. Far from receiving the kind of training he may have expected as a soldier in the British Army, he would probably have been sent almost immedietely overseas. Indeed, a stamp on his discharge papers says "embarked" 13th September 1915.

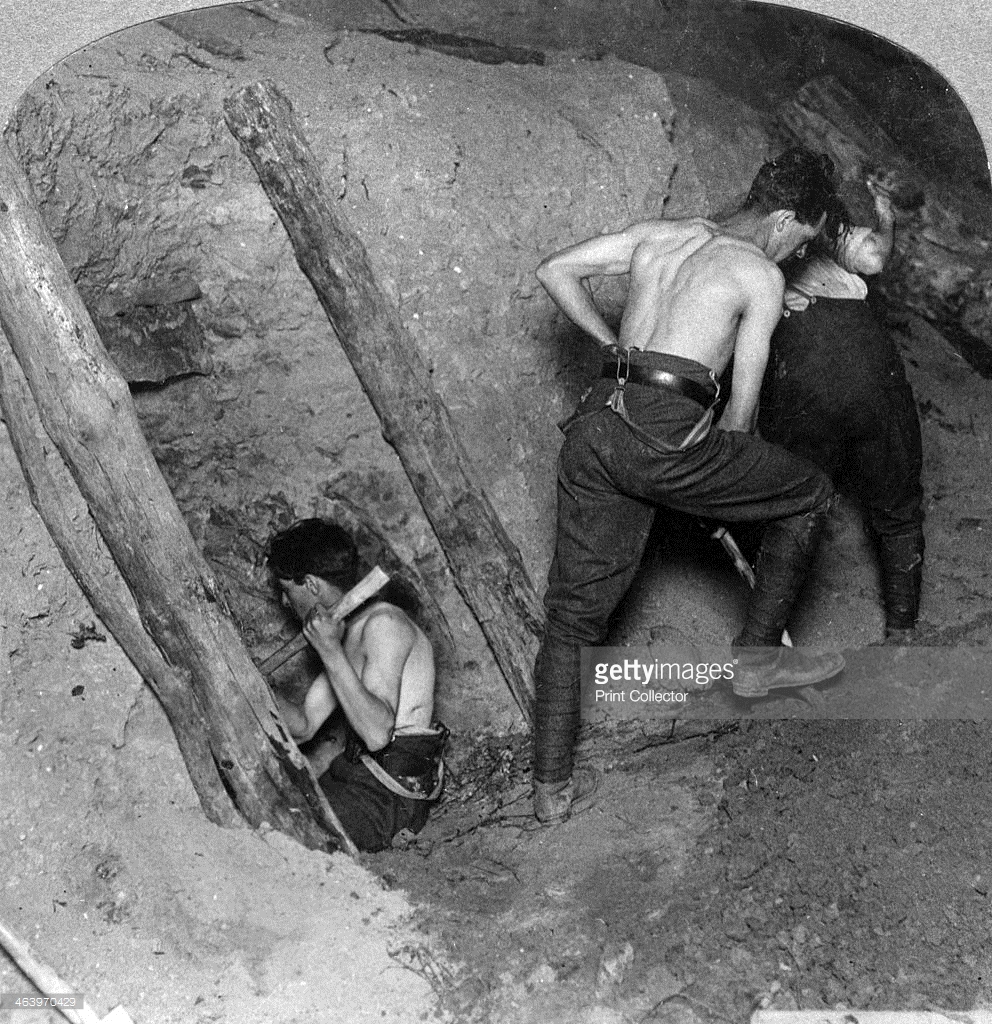

In December 1915 the 171st Tunnelling Coy. began work on a deep mine at trench 127 at St Yves. The name indicates the British trench were the mine began. The mine shaft was dug to a depth of 82 ft within four weeks, but after driving 1000ft of gallery, the engineers faced a sudden inrush of quicksand, and a concrete dam had to be constructed. The second attempt was ready by April 1916, packed with Ammonal (high explosive) charges 1300ft away from the initial shaft.

In February that year, another mine had been sunk by the 171st at trench 122, also at St Yves. This time there was a second tunnel branching off the main run and a total of 60,000lbs of high explosive was placed between the two tunnels, directly beneath the German lines at "Factory Farm".

The Messines Mines

In April 1916, the company was move to the Spanbroekmolen sector, facing the Messines Ridge. They took over the Spanbroekmolen mine from the 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company and drove the tunnel a further 1700ft towards the German lines in seven months. In February 1917 German counter-mining activities damaged the main tunnel, and a new gallery had to be cut, to re-join the main run. Mining was hampered by the influx of gas, and several miners were overcome by the fumes. Only a few hours before the deadline, the tunnel was complete and the ammonal (high explosive) charges were placed.

While the Spanbroekmolen mine was being dug, from January 1917 onwards, the 171st also continued work on the nearby Kruisstraat deep mine, which had already reached a depth of 1000ft through difficult sandy clay by the 250th, 182nd, 175th and the 3rd (Canadian) tunnelling companies. After a further 600ft drop was added to the shaft, 30,000lb of ammonal was placed, with a second charge of the same size placed at the end of a small branch tunnel around 160ft away from the first, under the German front line. That completed the original plans, but it was decided to place another charge below the German third line.Despite hitting tough clay, and the tunnel being inundated with water, requiring a sump to be added, Harry and the other tunnellers of the 171st tunnelling company completed a run of over half a mile from the initial shaft and placed another 30,000 lb ammonal charge. This was the longest of any of the Messines mines, After some German countermeasures damaged the tunnel, during the repairs, the oppurtunity was taken to add a forth charge of 19,500 lb of ammonal and all four charges were placed and ready by 9 may 1917.

Another mine was started by the 171st in January 1917 at Ontario Farm, also on the Messines frontline. It was again a complicated affair, as the ground selected was sandy clay. Despite setbacks which included building a pumping mechanism to add air to the mine, and remove water, as well as damming off a section of tunnel after a sudden flood, they reached their target under Ontario Farm at the end of May, and a 60,000 lb ammonal charge was placed there, with only one day to spare before the deadline.

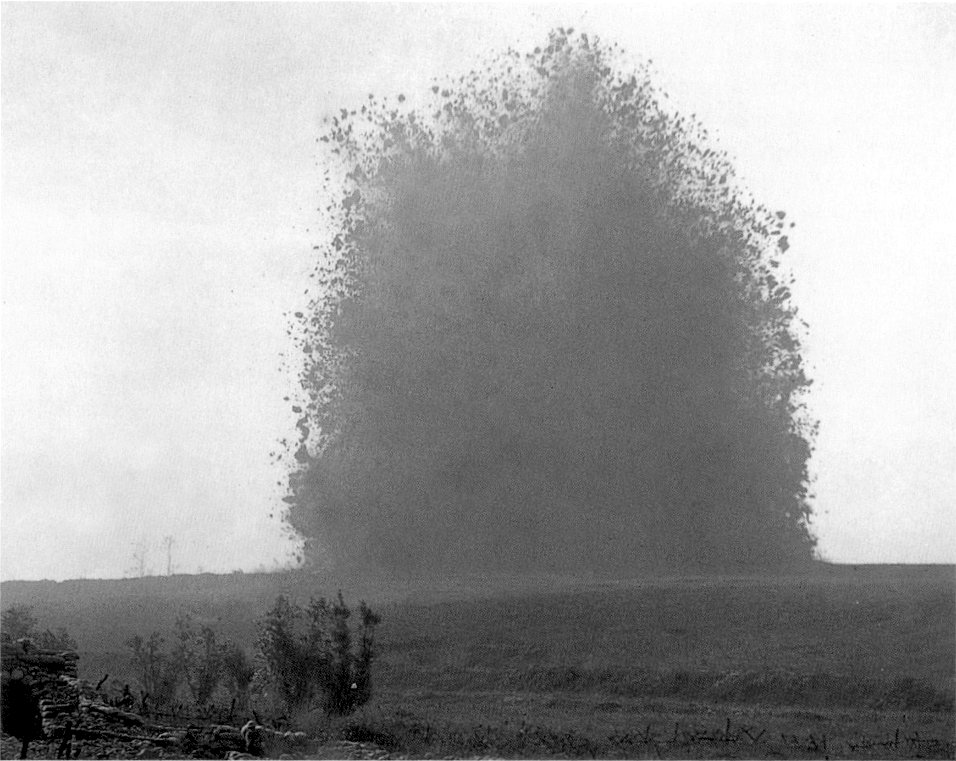

At 03:10hrs on the 7th June 1917 the Messines mines were detonated. In total 19 mines were simultaneously detonated to signal the start of the attack, which became known as The Battle of Messines. It remained the largest man-made explosion until the use of the nuclear bomb at Hiroshima in the closing stages of WW2. The explosions were audible in London. German deaths as a result of the mine is estimated at around 25,000, with upto 10,000 dying instantly. It was a ferocious example of what the mines placed by the tunnellers were capable of. See below for some photos of work on the mines, one of the detonations and the aftermath (click to enlarge).

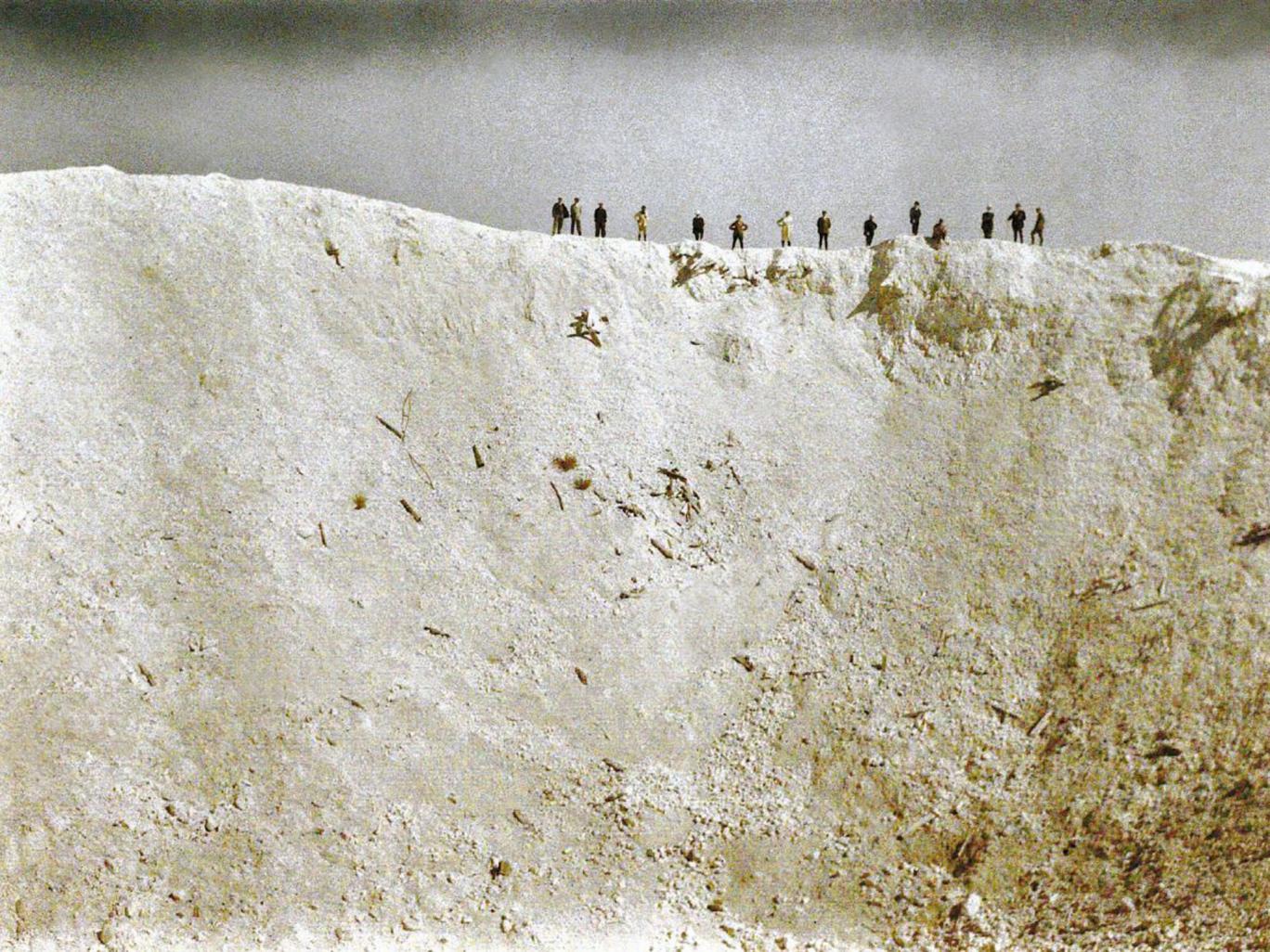

The Spanbroekmolen mine created a hole in the ground that measured 430 ft across. Like many of the other mine craters it is still visible today and is preserved as a memorial to those killed there, including some men of the 36th (Ulster) Division who were killed accidentally when the mine went off 15 seconds late and are buried at Lone Tree Cemetery near by. The Spanbroekmolen mine crater naturally filled with water 40ft deep, which is now know as the "Pool of Peace", and can been seen in images below (click to enlarge).

Vampire Dugout

The 171st Tunneling company stayed on the Ypres Salient, moving to Zonnebeke to begin work on the "Vampire" dugout near Ploygon Wood, designed to house 50 men plus one senior officer. Harry was one of 25,000 specialist tunnellers who, along with the support of 50,000 specialist infantry, dug 200 such dugouts on the Passchendaele ridge on the exposed ground captured after the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July–10 November 1917). By March 1918 more men lived underground, than reside above ground in the Ypres area today.

The 171st Tunnelling company took four months to complete Vampire, 46ft below ground, using I beams and reclaimed railway line in a D-type structure reinforced with stepped horizontal timber beams. It was occupied in early April 1918 first housing the 100th Brigade of the British 33rd Division, then the 16th King's Royal Rifle Corps and then the 9th Battalion Highland Light Infantry Regiment. After only a few weeks, the dugout was lost during the Battle of the Lys in April 1918. It was recaptured in September 1918, when its last occupants became the 2nd Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment.

This wonderous feat of engineering dug and constructed by Harry and his comrades of the 171st Tunnelling Company was feature on an episode of the BBC archealogical series "Time Team". The full episode is available on YouTube and the video is linked below.

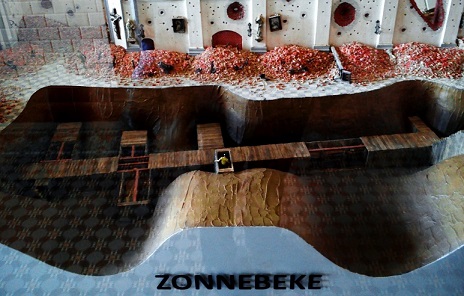

Zonnebeke Church Dugout

In March 1918, Harry relocated with the 171st Tunnelling company to the nearby ruins of the Zonnebeke parish church to construct a deep dugout below. This particular dugout was only discovered many decades later during archaeological excavations of the Augustinian abbey. a model of the dugout has been put on display in a nearby museum, and is pictured below (click to enlarge)

Spring Offensives

Shortly after the completion of Vampire and the Zonnebeke church dugouts in April 1918, the 171st and several other tunnelling companies had to leave their camp at Boeschepe, when the enemy broke through the Lys positions during the Spring Offensive. These units were then put on duties that included digging and wiring trenches over a long distance from Reningelst to near Saint-Omer.

Harry's Disciplinary Record

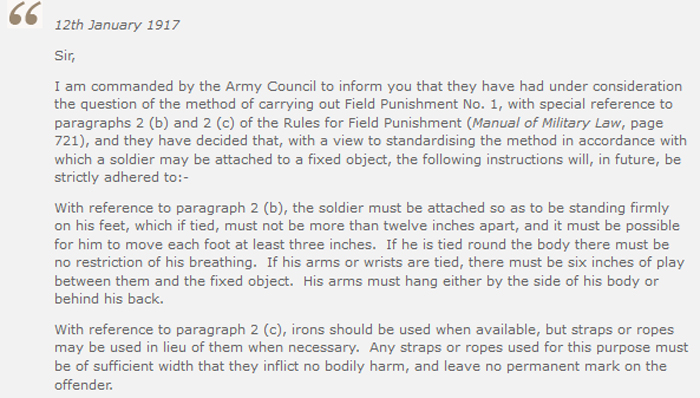

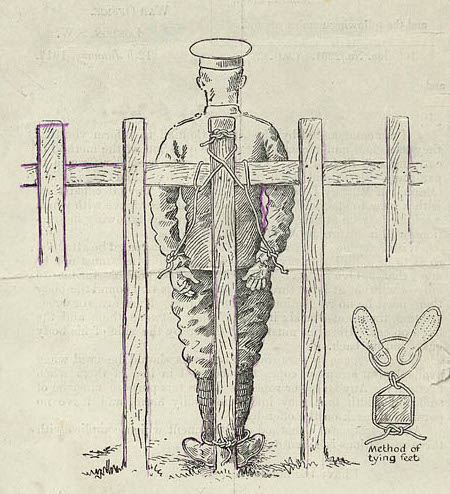

Whilst Harry was a very experienced and profficient miner and tunneller, he has a rather long and intriguing disciplinary record. In January 1916 he was absent without leave for four hours, returning back drunk he was awarded 10 days "close arrest", specifically FPNo1 (Field Punishment Number One).

Field Punishment No1 was a humiliating form of punishment which saw the soldier in question attached standing full-length to a fixed object - either a post or a gun wheel - for up to two hours a day (often one hour in the morning and another in the afternoon). Unlike imprisonment, regular duties could still be carried out in-between, and the field unit would not lose a man. Sometimes tied in a crucifix position. Stories abound of soldiers positioned to face the enemy lines, invariably out of range of enemy fire but allegedly not always so. If exposed to the sunshine this form of punishment proved ever more discomforting, quite aside from the constant problem of trench lice. If the soldier in question started to sag while attached to the post he would often be checked by military police. Similar stories persisted of commanding officers who abused regulations governing such punishment by tying soldiers' hands behind their back and suspending them by a rope tied around their wrists, their feet barely touching the ground. Such was the concern of abuse of the punishment, the War Office issued advisory orders to ensure the correct regulations were adhered to, this order, plus a representitive image of the punishment are shown below (click to enlarge).

On the 9th of May he was again AWOL for and hour and half, returning drunk, and again receiving FPNo1, this time for seven days.

For overstaying leave by 4 days in July 1916 he recieved an extremely harsh 90 days FPNo1. It was almost unheard of to receive more than 28 days FPNo1 at a time during the war, so it's testiment to Harry's invaluable tunnelling ability that 171st Company did not want to lose him. A lesser skilled man would have risked court martial and long-term improsonment for the repeat infractions he had committed until then.

However, Harry wasn't finished yet! In August 1916 he was docked 28 days pay for "Breaking away from parade without permission", not returning until an hour and a half later.

Harry appears to have stayed out of trouble for a year, until August 1917 when he was found to be drunk and was awarded 14 days of Field Punishment Number Two (similar to FPNo1, but usually restrained in irons, and not fixed to an immovable object).

Other than another couple of minor infractions for overstaying leave, his record shows nothing else except a couple of short stays in a field hospital,

Harry Devonport was finally discharged from the army on 21/01/1919, having been one of the approximately 275 men who served in the now famous 171st Tunnelling company. The war under no-mans land was frought with danger. The cold, dark, cramped conditions and danger of gas was just some of the daily problems a tunnelling sapper could face. There were numerous, bloody hand-to-hand altercations with German tunnellers, whom they frequently encountered. A large proportion of the tunnellers suffered greatly from post traumatic stress (shell shock) for the rest of their lives following their experiences of the war, many turning to alcoholism. Sadly, what happened to Harry after the war is a mystery. His 1914-15 Star and Victory Medal have at some point become seprated from the British War Medal. I am, however, looking to acquire the missing medals, should they, by any chance ever resurface.

More information about the secretive exploits of the tunnellers is still coming to light, as more dugouts and tunnels are discorved on the Western front. Sinkholes are appearing every year in the farmlands of France and Flanders, as the tunnels are reclaimed by the sand clay and mud. There is a memorial to the tunnellers and their exploits in Givenchy, France - pictured below (click to enlarge).

Harry Devonport - Medal Index Card

Harry Devonport - Discharge papers and disciplinary record (8 Page PDF)

Harry Devonport - British War and Victory Medal Roll

The Invicta Medal Museum (Online)

The Invicta Medal Museum (Online)